by Marnie Werner, VP Research

A unique opportunity?

For a printable version of this report, click here. To view the accompanying webinar, click here. To download the slides from the webinar presentation, click here.

After a year of COVID, spiking unemployment, closed schools, and restricted businesses, rural Minnesotans may be looking at a unique opportunity in economic development. Since the Great Recession, rural employers have been dealing with an ever-growing job vacancy rate, which we discussed in our recent report, “The pandemic paints a different employment picture in Greater Minnesota.” Now, at the beginning of 2021, we’ve been presented with a new and rare opportunity: we also have a larger-than-usual pool of unemployed workers. We now have the chance to match workers without job to jobs that need workers.

But a few things stand in the way of taking full advantage of this opportunity. The first issue we addressed in last month’s report. Most of Minnesota’s unemployed workers’ skills don’t match up with the skills rural employers currently need in health care services and our growing manufacturing sector. Many of the needed skills require training, and therefore, we need to make sure our retraining programs are ready for the challenge. Matching the right people with the right training programs to get them into good jobs would be a boon to young families looking to move to a community for the rural lifestyle.

The other piece, though, is much tougher to fix, and that piece is child care. The one thing holding rural Minnesota back from taking a serious leap forward economically is the lack of workers, and there are three things getting in the way of fixing that: a lack of child care, a lack of affordable housing, and a lack of transportation. The biggest of these is child care.

The trends

Last year finally brought into sharp focus just how important child care is to maintaining a functioning economy. As we noted in our original report on child care, “A Quiet Crisis,” in nearly 80% of Minnesota families, all parents work, and child care issues are the primary cause of absenteeism among American workers. Child care is indeed the infrastructure that keeps America working, and COVID-19 and 2020 made this painfully clear.

Licensed child care comes in two forms: center-based child care (CCC) and family, or in-home, child care (FCC). Because of economies of scale, family child care is far more prevalent in areas of sparse population, while child care centers are much more common in urban and suburban areas. In Minnesota, both types were growing fairly steadily until 2000. Around that time, something happened. The number of licensed centers kept growing, albeit modestly, particularly in urban areas, but the number of licensed family care providers started to plummet (Figure 1 & Table 1).

Figure 1: Change in center child care and family child care providers and capacity statewide, year-end 2000-2020.

Table 1: Between 2000 and 2020, center licenses and capacity grew statewide, while family child care went steadily down.

| Child Care Type | Change in licenses | Change in capacity |

|---|---|---|

| Family child care | -50% | -47% |

| Center child care | 8% | 6% |

In the Twin Cities, growth in center capacity between 2000 and 2019 was almost able to make up for the loss in family-based child care. The metro area ended 2019 with a net of -1,462 spaces (FCC and CCC capacity combined). 2020 set things back further with a net loss of an additional 1,200 spaces.

In Greater Minnesota, the net loss of child care capacity was much larger: more than 20,000 space were lost, even though population in most Greater Minnesota counties grew during that time. 2020 was barely a blip in the downward trend in family child care capacity (Table 2).

Table 2: Net change in child care capacity, 2000-2020.

| Greater MN | 2000 | 2020 | Net change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family child care | 90,686 | 55,231 | -35,455 |

| Center child care | 25,730 | 40,933 | 15,203 |

| Twin Cities metro | 2000 | 2020 | Net change |

| Family child care | 68,845 | 29,120 | -39,725 |

| Center child care | 60,779 | 97,816 | 37,037 |

| Total Greater MN capacity | 116,416 | 96,164 | -20,252 |

| Total Twin Cities capacity | 129,624 | 126,936 | -2,688 |

The loss in family child care is particularly troubling for rural areas. The sparse populations that characterize rural places make it more difficult to open child care centers, which usually require more children to achieve the level of revenue needed to pay for the higher startup and ongoing operating costs of a center. Family providers, who care for children in their homes, don’t require the building or the staff that centers do and therefore can operate financially with fewer children. For this reason, family child care has been the foundation of child care in rural Minnesota much more so than centers. While centers have been growing, family child care capacity has been falling faster.

While center capacity increased as a share of overall capacity in Greater Minnesota, the number of centers actually fell, from 692 in 2000 to 625 in 2012, back up to 674 in 2019, then back down to 654 at the end of 2020. What this trend overall implies is that on average each center is getting bigger, but we are not necessarily getting more of them. Child care centers in the seven-county metro area are getting bigger on average as well, but while their numbers also dropped for a while between 2000 and 2010, they started increasing again, peaking at 1,104 in 2019, only to drop back to 1,072 in 2020.

In Greater Minnesota, larger but fewer centers means that child care is concentrating in areas that can support them, larger towns and cities with an ample pool of families. That doesn’t help families that live outside those centers’ range. Adding capacity in Mankato doesn’t help a family fifty miles away in rural Mountain Lake unless one of the parents works in or near Mankato. This is the reason we hear so many firsthand experiences of parents driving their child 30 miles to a provider, then 20 miles back in to get to work.

Regional loss

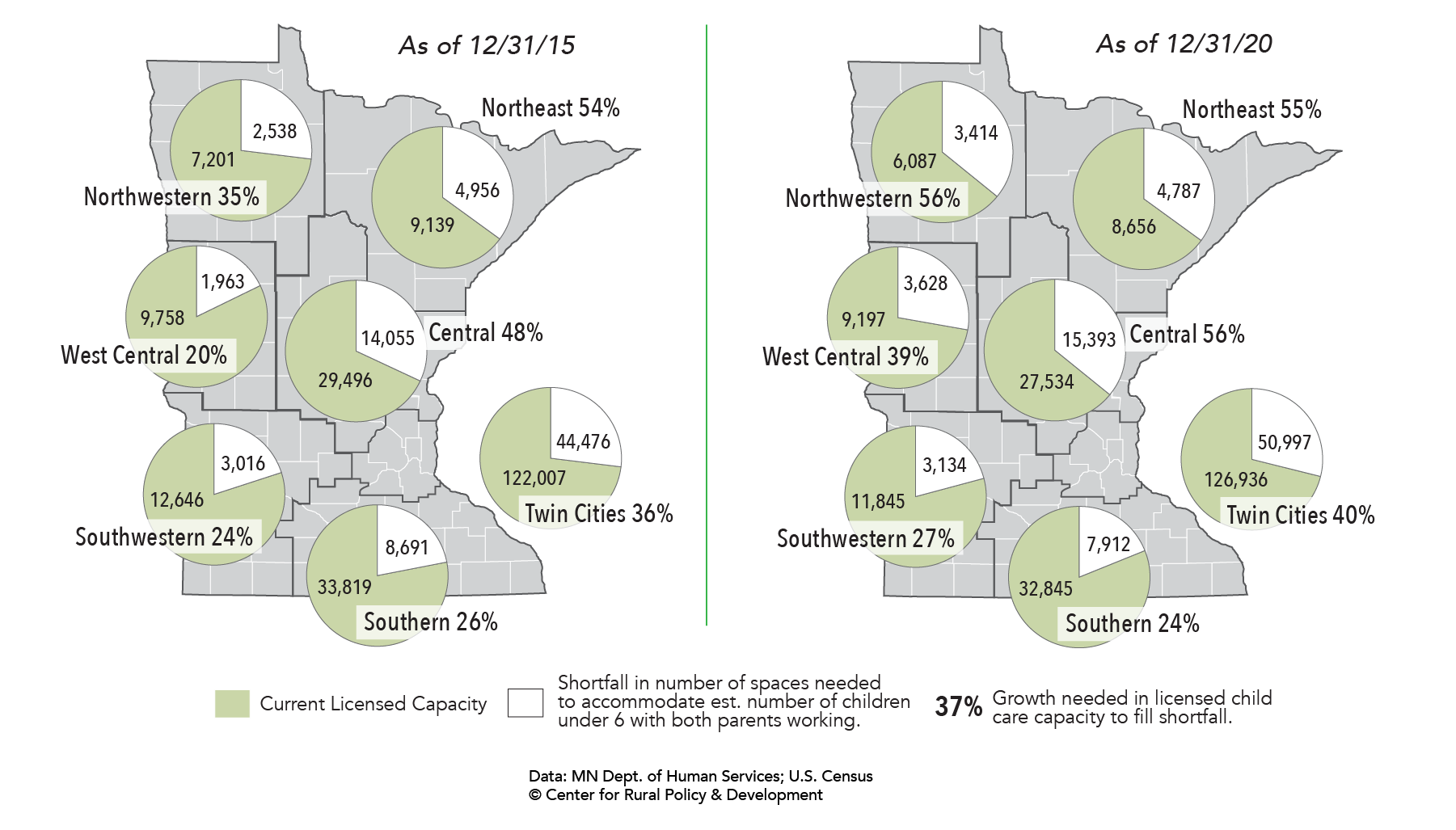

In 2016, we presented a graphic showing the shortfall in child care capacity for each region of the state. Figure 2 shows that graphic and an updated version. In four of the seven regions, the child care shortage and the amount the region would need to grow its child care capacity stayed fairly steady, not much better and not much worse. In three regions, however—Central, West Central and Northwest, the shortfall truly intensified. Table 3 also illustrates the trend by region between 2000 and 2020. In the Twin Cities area, capacity grew, but so did the region’s population of under-6 children. In the West Central region, the estimated number of children needing child care also grew, by more than 1,100, but child care capacity dropped by over 500 spaces.

Figure 2: Child care capacity, shortfall, and the amount needed to grow capacity to make up for that shortfall, by Minnesota Initiative Foundation region, 2015 and 2020. Licensed child care capacity versus the estimated number of children under 6 with both or all parents in the workforce.

Table 3: Net change in center and family child care capacity by region, 2000-2020.

| MIF Region | Change in center capacity | Change in family child care capacity | Change in combined capacity |

|---|---|---|---|

| East Central | 60% | -35% | -13% |

| Northeast | 37% | -54% | -27% |

| Northwest | -3% | -36% | -30% |

| Southern | 104% | -41% | -10% |

| Southwest | 34% | -40% | -25% |

| West Central | 16% | -32% | -22% |

| Twin Cities | 61% | -58% | -2% |

What happened in 2020?

2020 was a particularly rough year for child care (see Table 4). As businesses and schools shut down, everything suddenly moved to the home. Child care providers found themselves adapting quickly to new rules that would allow them to stay open to care for the children of essential workers, even while they faced a substantial loss in revenue.

Table 4: Net change in center and family licenses and capacity between year-end 2019 and year-end 2020.

| MIF Region | Center child care licenses | Family child care licenses | Center child care capacity | Family child care capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Central | -6 | -61 | 115 | -788 |

| Northeast | -7 | -29 | -141 | -345 |

| Northwest | 2 | -30 | 117 | -363 |

| Southern | -3 | -62 | 464 | -777 |

| Southwest | -5 | -27 | 89 | -252 |

| West Central | -1 | 2 | 144 | -54 |

| Twin Cities | -32 | -138 | 287 | -1,513 |

| Total | -52 | -345 | 1,075 | -4,092 |

Parents kept their children home from child care for a number of reasons: the parent(s) lost their jobs and couldn’t afford child care anymore; they were working from home and decided to save on child care costs by keeping the kids home, too; they feared they or their children would be infected; or their child was sick or quarantined due to exposure to COVID and had to stay home. Often, though, the reason their children stayed home was because their child care was no longer available. And COVID added a new quirk to the problem. In normal times, a family that couldn’t access child care would often call on friends or family for help. In the pandemic, though, families have become reluctant to ask the grandparents for help because of a fear of infecting them, thus closing off that avenue as well.

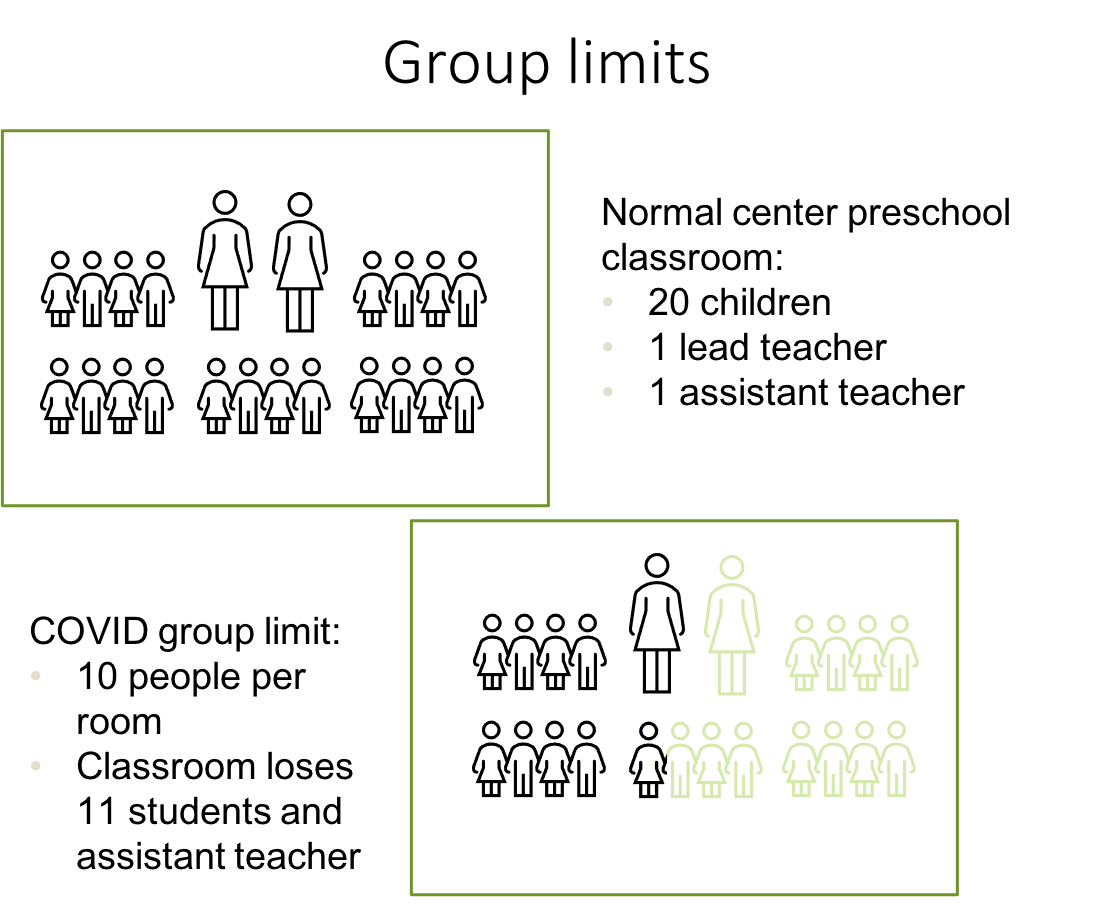

For child care centers, restrictions on the number of people per room—group limits—had the potential for the largest impact (see Figure 4). Under normal circumstances, state child care quotas limit the number of children per adult in a child care facility, with different numbers for different age groups. For example, the quota for the preschool age group is ten children per adult. Therefore, a typical classroom might have twenty preschoolers and two teachers, a lead teacher and an assistant teacher.

Mandating a 10-persons-per-room limit would have wreaked havoc on centers’ revenue and staffing and was therefore strongly recommended but not required by state health officials. Using the preschool classroom example above, restricting the number of people in a room to ten would mean the classroom could have only nine children and one teacher, the lead teacher. If the center had an extra room, another lead teacher (not the assistant teacher) could take another nine children. But that would still leave two children without a classroom and the assistant teacher without a role. If the center didn’t have the extra room, the leftover children would be out of luck and have to stay home.[i]

Figure 4: Group limits and their impact on centers.

For family providers, group limits weren’t as much of an issue since they generally care for fewer than ten children at any one time. They faced other issues, however: children kept home were a big issue, but school closures also created difficulties. Providers were asked to look after school-age children who would normally be in school, and providers often felt obligated to help them with their online classes. School-age children also brought with them higher expenses in food and other supplies needed for this different age group.

Anticipating the impact on child care revenue, the state issued emergency child care grants in three rounds to center and family providers using federal CARES Act funds. The Minnesota Initiative Foundations also created a fund and awarded grants. These grants didn’t save every provider, but they seem to have limited the damage in Minnesota considerably compared to other states.

Moving on from 2020: Quick fixes for 2021 to keep child care intact

The tribulations of 2020 aren’t over for child care providers. As more people are vaccinated and once unemployment benefits end, there will be a rush of people wanting to get back to work and back to workplaces, but the child care shortage will still be with us. We may also have to deal with intermittent waves of COVID infections as new variants roll through, requiring some restrictions again, albeit on a smaller scale.

And Greater Minnesota still sits with thousands of open jobs and shrinking child care capacity. Around the state, thousands of workers will be looking for new and maybe even better jobs than they had before, hopefully in Greater Minnesota. Will the child care providers who closed in 2020 reopen? What will incentivize new providers to step up?

Greater Minnesota will need a robust workforce development system to match people with jobs and a robust child care network to make it possible for workers and their families to take the jobs of their choice and live in the community of their choice without the stress of wondering what they will do for child care. So what do we do next?

First, we make sure our current child care system stays intact.

The emergency child care grants awarded by the state and the Initiative Foundations during 2020 have been a lifeline for providers, said Lynn Haglin, vice president and KIDS PLUS director at the Northland Foundation in Duluth, one of the six Minnesota Initiative Foundations. With very little margin for error, both family and center-based providers needed the monthly infusion of cash to be able to keep the doors open to care for the children of essential workers. Until group limits are lifted and providers can operate at normal enrollments again, continuing these grants will be crucial. Currently the state is counting on another round of COVID emergency money from the federal government to provide dollars for future emergency grants after the current round of grants run out.

If those federal funds don’t materialize, a priority will be to find funds to keep as many providers as possible in business. The private sector can help. While many businesses around the state are struggling to stay afloat, others are doing well. One suggestion would be for them to form a special child care philanthropy fund, perhaps working with the Initiative Foundations or other community foundations around the state to help disburse grants to child care providers.

Also, once restrictions are lifted and unemployment benefits end, there will be a need to match workers with jobs. As our workforce report pointed out, many of those workers may want to explore the vacant jobs waiting for them in Greater Minnesota. Those workers, however, probably don’t have the skills needed for those jobs. The state already has a robust system of workforce development and training programs around the state that will play a big role in making these matches work. However, workers with families may need help paying for child care while they participate in retraining and other education programs.

Programs like the Minnesota Family Investment Program provide subsidies to very low-income families to pay for child care while the parent is retraining. However, the scope of the MFIP subsidy and that of the other CCAP programs may need to be expanded to avoid income cliffs. If a family’s income excludes them from using MFIP or the Basic Sliding Fee child care program but they still can’t afford child care or can’t find it, it could be a major deterrent for them.

Usually, a family is tapered off child care subsidies as their income increases, until at some point they are earning enough to not qualify for subsidies at all. However, their income may still not be high enough to afford child care in their area. At that point, they are out of luck and so are the businesses that may have hired these workers. Here is another opportunity for not just the state, but local businesses and even communities to sponsor potential workers by supporting their retraining and the move to their new community by helping them find and pay for child care.

Beyond 2020: How do we fix child care for the long term?

As we get through 2021 and 2022 and things get back to normal, what then? Is “normal” where child care is concerned where we want to be?

Here again we have another opportunity staring us in the face: the opportunity to fix child care altogether. That may sound outrageous—after all, the solution to our child care crisis has eluded not just policy makers in Minnesota but all over the United States. But historically, times of great upheaval can turn out to be times of great opportunity for those who are prepared and looking out for it.

After the pandemic, we’ll be focusing on fixing our economy, and child care will have to be a part of that. But it can’t be an afterthought. Bringing it back to 2019 levels of providers is still far below 2000 levels and below what would be deemed inadequate. To fix child care and not just continue to patch it, we may need something akin to a Marshall Plan, which will require concentrated focus, a lot of money, and a great deal of will and commitment to get it done.

Right now, we have some breathing space before people need to find jobs and get back to work. Now is a good time to work on the beginnings of a permanent solution instead of once again reaching for the band-aids. Here are some places we recommend starting.

- Decide what child care is. Is it a business? Is it a school? Can it be both? Can it be one or the other? Is child care a highly regulated private business or an underfunded public school? One or the other—or variations in between—might work better for some communities than others, but whatever it is, we need to decide, even if that’s deciding to let communities decide. Providers live with a great deal of ambiguity that adds stress to an already stressful job.

- Continue to monitor child care policy for usefulness and unintended side effects. Our survey of providers taken in 2018 recorded numerous examples of regulations that, though they were well intended, ended up adding levels of hassle to already-stressed providers. In 2019, the Minnesota Legislature passed policy that addressed many of the hassle factors. From making it legal for providers to allow their kids to reuse their own reusable water bottles and sippy cups to determining that a family child care provider’s own children who live in the same home with her don’t need to have background checks except under very specific circumstances, the responsiveness of the Legislature is to be commended. The changes went a long way in addressing many policies that may have seemed inconsequential to someone not in child care but were adding to both center and family providers’ stress. Once the Legislature can move on to non-emergency policies, we recommend regularly monitoring existing policy and screening proposed policy from the perspective of the provider, the child and their family, all while maintaining safety. Click here for a more extensive summary of policy changes made in 2019 and 2020.

- Remember family providers. Family providers are the backbone of child care in Greater Minnesota, and yet we have half the number today that we had in 2000, leaving most rural regions child care deserts, even though Greater Minnesota’s population has increased. Until it becomes more affordable and feasible to start centers in areas of sparse population, family providers will continue to be needed. Another creation of the 2019 legislative session was the Family Child Care Task Force, a legislative task force made up of child care experts, state officials, child care providers and parents. Their task was to discuss the many identified problems contributing to the decrease in family child care numbers and to figure out some solutions. Despite being interrupted by COVID, the FCCTF met on a regular basis and just recently turned in their final report—on time.

- Don’t allow reimbursement rates to stagnate again. The “reimbursement rate” refers to Child Care Assistance Program subsidies that help low-income families pay for child care. Instead of going directly to the family, this subsidy is paid directly to the provider on behalf of the family. It is an important source of revenue, especially in child care deserts, where families tend to be lower income. Since 2003, providers who depend on child care reimbursement rates have had a rocky path. That year, rates were frozen through 2005 while the Office of the Legislative Auditor investigated suspect practices by state agencies in disbursing CCAP payments. Rates were unfrozen in 2005 and raised slightly in 2006, but then they were reduced by 2.5% in 2011. In 2014, rates were raised back to their 2006 level with a slight increase for some counties. Finally, in 2020, reimbursement rates were given a substantial boost. But rates stayed essentially the same or decreased for providers for 14 years between 2006 and 2020. The legislation also allocated funds for fiscal years 2021, 2022 and 2023.

- Child care desert premium. Right now, it’s difficult to determine the impact the new higher reimbursement rates might be having since the pandemic has been keeping revenue artificially low for many providers. Once things return to normal, though, the new higher rates may still not be enough for providers in child care deserts to survive. To help with the dysfunctional markets that create child care deserts in rural communities and urban neighborhoods, we propose exploring the idea of adding a child care desert premium or differential to the current reimbursement rate, similar to and on top of the premium a provider receives for Parent Aware Star ratings. It would be an additional boost for providers in those areas where child care facilities have particular difficulty developing naturally, and it would not only help existing providers stay in business, it could incentivize new providers to enter the business.

- Involve all stakeholders in community discussions, especially private-sector businesses. Child care shortages will often need to be solved at the community level, with all stakeholders coming together to discuss the issue and look for solutions. Rarely has one sector been able to solve the problem itself. Employers especially need to be involved. Employers have high stakes in the child care infrastructure. The number of stories are rising of employers who have finally found someone to fill an important, long-vacant position at their company only to have the family leave because they couldn’t find child care locally. Child care, along with housing and transportation, are the three biggest barriers to finding workers right now, says Vicki Leaderbrand of the Rural Minnesota Concentrated Employment Program in Detroit Lakes. RMCEP provides services to help match employers with potential employees through retraining, career counseling and other programs. Without child care, workers are cut off from what could be a new career. It also cuts off Greater Minnesota employers, from manufacturers to colleges to clinics and hospitals, from the people they need to grow their businesses.

Despite how important child care is to employees, though, employers in general have been slow to step in and get involved with finding solutions. Some of Minnesota’s largest companies do help with child care. Taylor Corporation, a major employer in south central Minnesota, has been providing deeply subsidized child care as a benefit to its employees for forty years. The center’s staff are Taylor Corporation employees. Harmony Enterprises in Harmony, MN, built its own daycare center in 2016, as did Gardonville Telecom in Brandon, MN, in 2014. Not every business can afford to open its own center, especially smaller companies, but there are other ways employers can contribute to creating a stable environment for child care providers: “reserving” slots with a local provider, contributing funds or space or other resources to a community project, or providing a child care allowance to employees.

- Allow for creativity. In an effort to keep children safe and increase learning standards, sometimes policy can become too rigid, as we saw in policy issues that were addressed in 2019. In a situation where regular market forces don’t work, however, businesses need to be able to think creatively to come up with ideas that solve problems. For example, child care in or connected to schools and senior living facilities are serving infants to preschoolers by helping reduce expensive overhead, allowing the provider to spend more on staff wages. In some models where the school becomes the child care provider, the child care staffers are also employees of the school district and are eligible for health benefits, a rare thing in child care, while in other models, they are not employees but may still have access to benefits.

- Allow for flexibility. The pod model is a new type of license for family child care providers that allows multiple providers to operate in one building without operating as a center. Providers run their programs separately, but they share the overhead costs that can make opening and operating a center prohibitively expensive in rural areas. This model could be more attractive to potential providers who don’t want to start a center but also don’t want to operate their child care business in their homes. This kind of flexibility in policy makes innovation possible, and that leads to solutions.

- Allow for experimentation. One of the most exciting developments in child care is the partnership that has developed between eight north central Minnesota counties and Sourcewell, a regional service cooperative located in Staples. The idea came out of a routine meeting of county social service directors discussing whether they could combine their resources in some way to provide better county licensing services. Most of the five counties in Sourcewell’s region could devote only part of a full-time position to county licensing, whose primary role is to help family child care providers become licensed and to conduct inspections. They eventually approached Sourcewell to see if their service cooperative could help somehow. Regional service cooperatives have been offering bulk purchasing and technical support to school districts and counties throughout Minnesota for decades. Working together with the Minnesota Department of Human Services, the counties and Sourcewell eventually developed a formal partnership. Sourcewell provides licensing services for these counties and offers an annual conference for family child care providers. The partnership has expanded from the original five counties in Sourcewell’s region (Region 5) to include three more counties located in Region 4. While the counties are still responsible for the enforcement of any infractions, Sourcewell is able to provide the full attention county licensing requires.

Is it time?

Child care is no longer a luxury. It is an economic development tool and an indispensable part of our economic infrastructure, especially in Greater Minnesota. We are at a point where with focus, motivation and will, we could have real impact on our child care crisis.

[i] Grunewald, Rob, “How a COVID-19 10-person group limit affects Minnesota’s child care providers,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, June 24, 2020.

Revised July 7, 2021. This report originally stated that group limits were required for child care centers, which was incorrect. They were only strongly recommended.